As of October 11, 2024, 100.78 million birds have been affected by the current highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreak which began on February 8, 2022. A total of 1,178 flocks have been affected in 48 states. Of those, 509 flocks have been commercial, and 669 flocks have been backyard. In addition, since March 25, 2024, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has confirmed HPAI in 300 dairy herds in fourteen states (Table 1) across the U.S. California has quickly taken the lead in confirmed cases with 100 cases being reported since the first three cases were confirmed on August 30,2024. Confirmations were made via milk samples as well as nasal swabs and viral genome sequencing of the affected herds. USDA has confirmed that the detections in dairy cows, which started in Texas, appear to have been introduced by wild birds; however, the Department continues to conduct an epidemiological investigation into how the virus is being transmitted among dairy herds and, so far, there is no conclusive evidence as to how this is happening. The latest USDA report on disease spread between dairy cattle farms found multiple direct and indirect transmission routes.

Table 1. Confirmed states with HPAI in dairy herds and number of cases per state (October 11, 2024).

| State | Number of confirmed cases |

| California | 100 |

| Colorado | 64 |

| Idaho | 34 |

| Iowa | 13 |

| Kansas | 4 |

| Michigan | 29 |

| Minnesota | 9 |

| New Mexico | 9 |

| North Carolina | 1 |

| Ohio | 1 |

| Oklahoma | 2 |

| South Dakota | 7 |

| Texas | 26 |

| Wyoming | 1 |

The milk supply remains safe. The USDA, CDC, FDA, and state health authorities all have affirmed the safety of the U.S. commercial milk supply. The federal Grade “A” Pasteurized Milk Ordinance (PMO) is the global standard for milk safety, ensuring no milk from cows exposed to HPAI or other illnesses enters the food supply and should milk from any asymptomatic dairy cow enter a processing facility, pasteurization will destroy HPAI as well as other viruses and pathogens. In keeping with the PMO, milk from sick cows must be collected separately and is not allowed to enter the food supply. This means affected dairy cows are segregated, as is normal practice with any animal health concern, and their milk does not enter the food supply. Milk is then pasteurized (subjected to high heat treatment) to kill all harmful pathogenic bacteria and other microorganisms, including HPAI and other viruses. Viral fragments detected by lab tests following pasteurization are evidence that pasteurization has effectively destroyed HPAI; these fragments have no impact on human health. All pasteurized milk and dairy products are safe.

Dairy farmers who observe clinical signs in their herd should immediately contact their veterinarian. Veterinarians who observe these clinical signs and have ruled out other diagnoses on a client’s farm should contact the state veterinarian and plan to submit a complete set of samples to be tested at a diagnostic laboratory. USDA has told the dairy community and practitioners that cattle are expected to fully recover in a few weeks and there is no need to cull dairy cows because HPAI poses a low risk to human health. While HPAI is fatal in about 90-100 percent of chickens, there has been little to no mortality reported in dairy cows. Cows recover in about two weeks. Moreover, there are no widespread impacts on dairy production today. USDA will continue to share information as they learn more.

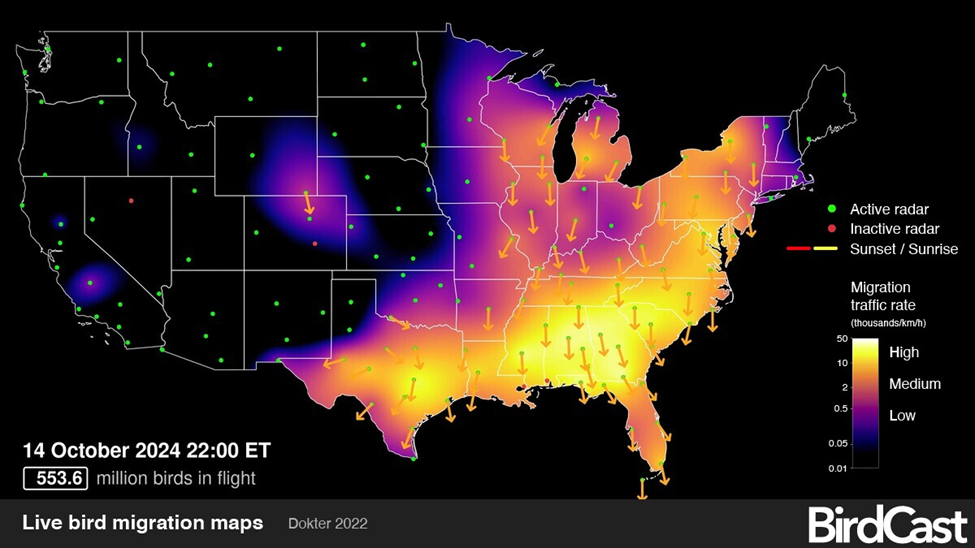

Dairy farmers must implement enhanced biosecurity protocols on their farms, limiting the amount of traffic into and out of their properties and restricting visits to employees and essential personnel. Avian influenza is an animal health issue, and the risk to humans remains low. However, as USDA advises, people with close or prolonged, unprotected exposures to infected birds or other animals (including livestock), or to environments contaminated by infected birds or other animals, are at greater risk of infection. We are currently in the height of waterfowl migration season. HPAI is transmitted through droppings or nasal secretions of infected birds, which can contaminate water, feed, dust, and soil. The virus may also be spread, at least for short distances, by wind. People may carry the virus on their shoes, clothes, equipment, and vehicles. With fall migration season underway (Figure 1) and cooler seasonal temperatures arriving, the HPAI threat will increase over what we have seen throughout the summer.

Continue to remain vigilant, maintain good biosecurity, and report anything that seems out of the ordinary, health wise, with your poultry flock or dairy herd to the proper authorities.

UT Animal Science/Extension continues to monitor the situation and is committed to supporting our stakeholders and clientele throughout this evolving event. As stewards of animal health and welfare across the livestock and poultry industries, our team of experts are constantly reviewing this changing and challenging situation and will continue to provide updates as necessary.